Juan Flores and "Las Manillas" - OCHS History Hike, 4/20/2024

Juan Flores and “Las Manillas”

OCHS History Hike 4/20/2024

Juan Flores was born in Mission Santa Clara near the pueblo of San Jose on January 3, 1834. He was the fourth child of José María Flores, an artilleryman in the Spanish military born at Mission San Gabriel in 1796, and María Josefa Sepúlveda, who was born in San Francisco in 1804. He spent his childhood growing up in a typical Californio family in and around the pueblo of San Jose and received a decent education. Juan’s father died around 1850, just as the American era and Gold Rush started to significantly affect the Californios’ way of life. Juan was apparently working as a cook with some of his other family members during the census of 1852.

By 1855, however, Juan (from here on out referred to as Flores) had made his way south, perhaps as a cowhand with one of the many cattle drives from Southern California ranchos to Northern California markets to supply beef to San Francisco and the mines. That April, Flores and one Juan Gonzalez were arrested in the sleepy former-mission town of San Juan Capistrano for attempting to steal horses from Garnet Hardy, one of three brothers who ran a weekly stagecoach between Los Angeles and San Juan Capistrano. Flores was convicted of Grand Larceny and sent to San Quentin Prison.

At the time San Quentin had numerous prison breaks and Flores escaped in October of 1856 via a barge while gathering firewood. Soon after he joined another escapee, Jesus Espinosa, whom he may have known from his days in San Jose. Together they teamed with “Pancho” Daniel, Andres Fontes, and, in San Luis Obispo, Leonardo Lopez while making their way south, apparently with the intention of working as ranch hands.

When the small gang reached San Juan Capistrano in early 1857, however, Flores apparently couldn’t pass up on the opportunity to seek revenge on Garnet Hardy. Hardy arrived in town with his team of horses for his weekly supply run and was soon warned that Flores had returned and he and his gang were planning to kill him on the road back home. Hardy wrote a letter to his brother in Los Angeles who informed the county sheriff, James Barton, that there was trouble brewing at San Juan Capistrano.

Meanwhile Flores and his gang recruited two locals, Juan Catabo and fifteen-year-old Antonio “Chino” Varelas, and perhaps one or two others. The gang now numbered as many as nine and referred to themselves as “las Manillas,” meaning “the Handcuffs,” which was a nod to some of them being escaped convicts. Soon the gang started wreaking havoc in town, stealing a gun from a local shop owner and shooting at a saloon (today’s Blas Aguilar Adobe). As chaos erupted over the town, a German shopkeeper, George Pflugardt, was murdered. Las Manillas had crossed a point of no return.

Meanwhile in Los Angeles, Sheriff Barton organized a small posse including Alfred Hardy (Garnet’s brother), Constables William H. Little, Charles K. Baker, Frank H. Alexander, and Charles F. Daly, and a Frenchman who had once been a vaquero on the San Joaquin Rancho. Together they left for San Juan Capistrano.

On January 23, 1857, Las Manillas attacked Barton’s posse near Barton Mound (near today’s intersection of the 133 and 405 Freeways), killing Sheriff Barton and constables Little, Baker, and Daly. Alfred Hardy escaped back to Los Angeles and Charles K. Baker headed for El Monte.

Los Angeles was thrown into a complete state of hysteria. Soon the high-profile and wealthy Californios formed a posse under the command of Andrés Pico and Tómas Sánchez and the citizens of El Monte (mostly Texans) formed their own posse under the direction of Dr. Frank Gentry. Their combined numbers eventually reached about 120 men.

Intelligence was gathered in San Juan Capistrano that indicated that the bulk of Las Manillas fled to the head of Santiago Canyon. A plan was organized to send Indigenous scouts, under the command of Manuelito Cota, to the top of the Santa Ana Mountains to protect the mountain passes. The El Monte company would ride to today’s Orange and head up Santiago Canyon while the Californio company would ride up Trabuco and Aliso Canyons and drop down into Santiago Canyon near today’s Modjeska Canyon. This was a classic pincer’s movement designed to catch the gang in Santiago Canyon.

On January 30, 1857, the Californio company discovered the trail of Flores and five of his companions and followed it into upper Santiago Canyon. Their trail soon reached a steep ridge between today’s Harding and Santiago Canyons, which is today’s Flores Peak. The robbers shot their guns back at Pico and his men in pursuit, who also returned fire, but the brush was too thick to make a run on the gang members. The El Monte company arrived that evening and the combined posses met near today’s fire station in Modjeska Canyon. Dr. Gentry arrayed his men along the southern base of the ridge towards today’s Tucker Wildlife Sanctuary while another of the El Monte company, Bethel Coopwood, along with Tómas Sánchez of the Californio company and six others, dismounted their horses and pursued Las Manillas up the steep and brushy ridge on foot. While doing so they encountered “Chino” Varela, who was taken into custody.

Sánchez, Coopwood, and their men continued through the thick brush while Las Manillas would occasionally rise above them from behind the chaparral and rapidly fire their guns before ducking back down. Las Manillas made their way to the top of the mountain, apparently with their horses, while their pursuers climbed on foot up a bottleneck to reach the summit. The rest of their men watched anxiously from below. Suddenly the guns silenced. When the possemen finally reached the top they descended to a shelf below and found but one gang member there, Juan Catabo, who surrendered. But what of the rest? Juan Flores, Jesus Espinosa, and Leonardo Lopez had tied their riatas together and slid down a rocky precipice hundreds of feet into the darkness below. While doing so their rope broke and Flores fell into the steep wall of the mountain, causing his cap and ball revolver to go off, injuring his hand.

Meanwhile, Dr. Gentry’s men caught another gang member, Francisco “Ardillero,” escaping down the south side of the ridge. When the posses recombined near today's fire station they were stunned that Flores was able to escape. They also learned that “Ardillero” had joined the gang after they had committed their crimes. Only three of the gang, “Chino” Varela, Juan Catabo, and Francisco Ardillero, were now in custody and the pursuit continued.

Dr. Gentry finally located Flores’ trail two days later on February 1, chasing him and his two companions for three miles before catching them in a cajon in Santiago Canyon, possibly below today’s Robber’s Peak (which may explain the derivation of the name). They were taken to Teodosio Yorba’s rancho near Olive (near the intersection of the 55 and 91 Freeways). Pico and the Californio company started down Santiago Canyon to meet them at Yorba’s the next day. But Flores wasn’t done making great escapes. He convinced the El Monte company guards that his hand injury required them to only loosely tie his hands together. In the middle of the night he freed himself, untied Espinosa and Lopez, and all three escaped into the darkness through today’s Anaheim and Fullerton.

Pico was informed of their escape while he and the Californio company were on their way to Yorba’s rancho the next day. He decided to hang his two prisoners, Juan Catabo and Francisco “Ardillero,” on a tree that still survives in Precitas Canyon near the intersection of today’s Santiago Canyon Road and the 241 Toll Road. As was custom in the Spanish and Mexican days, he had the ears of the executed men cut off and taken to Los Angeles as proof of their deaths. “Chino,” on the other hand, was let go on account that his father was famous from an incident that had occurred during the Mexican American War following the Battle of Chino (but that’s a different story).

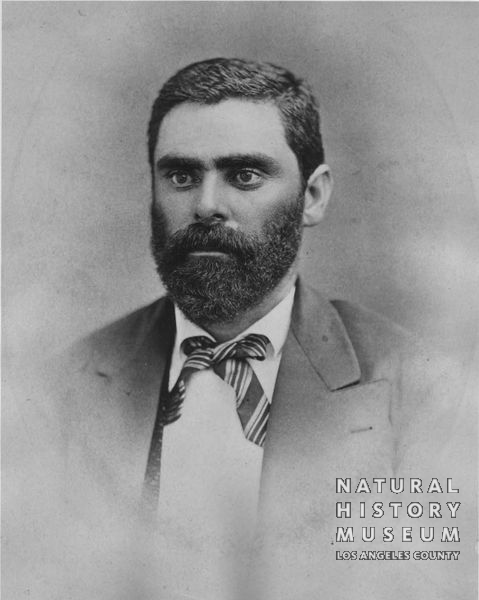

Antonio "Chino" Varela, the only known of Las Manillas to have an extent photograph. He was caught on today's Flores Peak at the same time Juan Flores, Jesus Espinoza, and Leonardo Lopez brazenly escaped into the night by descending the rocky cliff of the peak using their riatas. (Seaver Center for Western History Research)

Flores was finally caught northwest of Los Angeles at Santa Susana Pass (then called Simi Pass) and publicly hanged on Fort Moore Hill. Jesus Espinosa was caught shortly thereafter near Mission San Buenaventura and hung at that mission. Leonardo Lopez was finally caught the next year and stood trial in Los Angeles. During the trial it was revealed that his real name was Luciano Tapia and that he was from San Luis Obispo. He was also publicly hanged in Los Angeles.

Other gang members were also brought to justice. “Pancho” Daniel was hanged in Los Angeles in 1858 by a mob while awaiting trial. “Chino” Varela got into trouble in Baja California, possibly as part of another gang that included Andres Fontes. Varela’s good name, however, again saved him and he was apparently spared from sentencing, living out the rest of his life at the Rancho Camulos west of Santa Clarita. Andres Fontes, on the other hand, was apparently killed by the Baja authorities.

The events of Juan Flores and Las Manillas are an incredible episode in the history of the American West. They tie Orange County directly to the very history that inspired the Western genre of movies, television shows, literature, and video games. The reality of this history was a mixture of class struggles, lack of organized justice systems, violence, and the brutal consequences of a society experiencing incredibly rapid change. We should both be fascinated by the ruggedness of the sage-covered mountains, the horses, posses, gun fights, and escapes in the dusty and distant past, as well as reflective about the challenges throughout our history in creating a more fair and robust society.

Eric Plunkett, 2024

Part 6: The Great Stone Church (A future post)

Part 10: Richard Henry Dana at Dana Point